“A win-win situation is when both Pixy and Moro benefit from each other at the same time,” reads one entry in artist Pixy Liao’s book PIMO Dictionary (2018). “This situation is very hard to achieve.” Liao’s definition of “win-win” is less capitalist than others, such as the one describing the goal as to “maximize value creation.” The artist produced the dictionary, an intimate taxonomy of language, in collaboration with her lover Takahiro Morooka, or Moro. It emerged from a relationship that is in some ways unique—Liao and Morooka met as graduate students at the University of Memphis, across the globe from where either were raised, and now live as internationally exhibiting working artists—and in other ways like any other. Who, through the alchemy of oxytocin and shared time, has not developed a language that belongs to just them and their beloved? The dictionary, then, speaks to the nature of intimate collaboration, shared ownership, and the merits of stylized documentation—three themes that run throughout Liao’s oeuvre. Liao’s deeply collaborative exhibition Relationship Material, at the Art Institute of Chicago, highlights the play inherent in a mature relationship, challenges traditional notions of authorship as ownership, and dares to have fun with gendered elements of power.

Though Relationship Material is a solo show, Liao’s first in Chicago, the artist never purports to be an auteur. Its centerpiece is her decade-long, ongoing project Experimental Relationship, a series of posed photographs of Liao and Moro. Ultimately, there is no fixed artist-muse dynamic in these images, only roles the pair inhabit across time for fun and function. Liao’s artistic sensibility is supported by the curatorial vision of Yechen Zhao, a photography and media curator at the museum, who organized the show to treat Liao as one of two protagonists and embrace an ethics of collaboration. The show features not only work made under Liao’s name but also music by her and Moro’s experimental music project, PIMO, and a set of sculptures by Moro.

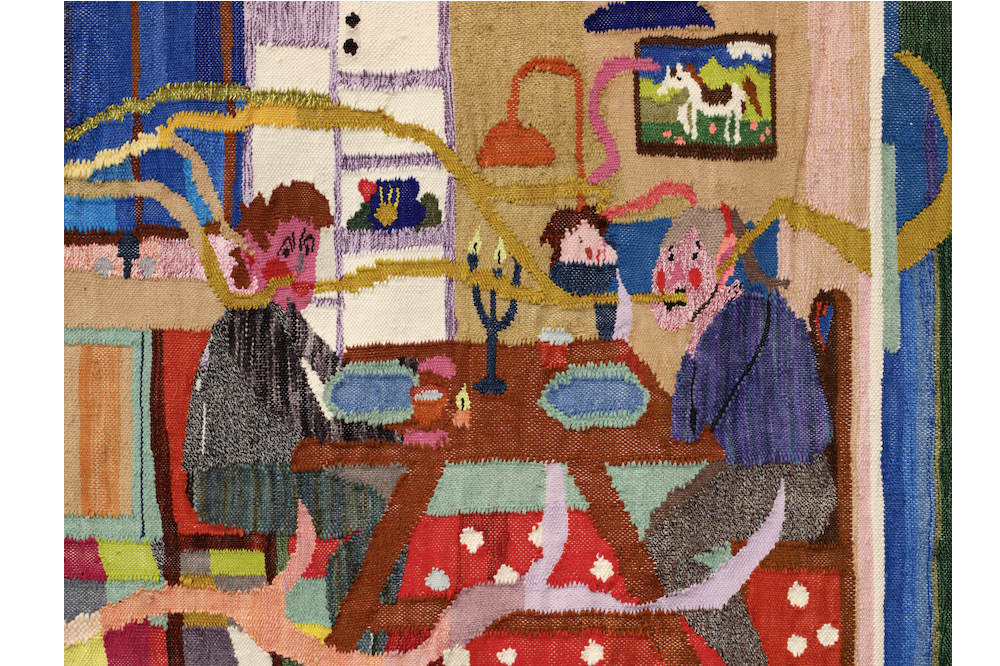

Pixy Liao, Liven up your conversation with a novel approach, 2007. Courtesy of the artist, © Pixy Liao.

Liao and Moro began shooting together in 2007, soon after meeting. Liao has stated that the mission of Experimental Relationship is to “reach a new equilibrium,” but she does not simply aim to invert heterosexual hierarchies. Rather than gesturing toward matriarchy, or some kitschy “what if women ruled the world” thought experiment, the collaborative tenderness of her work suggests a more wide-open pro-sexuality humanism. It underscores how impossible it is for two people who lie together for decades, who are invested in being in a humanizing relationship, to see each other within the increasingly strict stereotypes that define heterosexuality. Sometimes Moro and Liao appear to slip on these stereotypes like costumes, but then, in the next image, they have slipped on new costumes.

Liao’s images offer an ongoing critique of how a culture shaped by patriarchy reduces sexuality to clichés, in part because instead of relying on a prefab heterosexual division of labor, they portray and grow out of a dynamic partnership. Liao plays with the textures of heterosexual dating-advice culture through the titles of her photos—a number of earlier works are titled as though they are articles from Cosmopolitan. Start Your Day with a Good Breakfast Together (2009) features Pixy eating a papaya placed cheekily over Moro’s naked groin, both inverting racist erotic depictions of East Asian women’s bodies as “plates” and nodding to the fact that the two literally do eat breakfast together each morning (though of course not in this particular way). Transforming a typical breakfast scene into an absurd erotic setting framed by the dating-advice industrial complex ends up poking fun back at the hidden, taken-for-granted expectations of heterosexual life.

Moro is five years younger than Liao, and many of the photos parody traditional gender roles in which the patriarch is older and more powerful. In Story Time (2022), Liao perches on a chair reading Emmanuelle, an Orientalist erotic novel from the late twentieth century. She peeks stoically over the edge of the book to check on Moro, who kneels naked beside her, head cupped demurely in his right hand, expression neutral. They do not make eye contact. Liao plays with the role of a strict nanny, or a teacher, or perhaps a sexualized interpretation of one; her naked feet take center stage, her toes brushing the speckled floor. Her red dress is a pop of color against an otherwise muted palette (color often adds an erotic charge to Liao’s images—her red painted nails feature frequently). Both figures are backlit by sun streaming in from the window behind, which adds a warm, almost dreamlike cast to the already uncanny situation. In his left hand, Moro grips a trademark motif of the series—the snaking black cable attached to the camera’s shutter release—making visible the moment he gets the shot. This gesture speaks not only to submission but to necessity—the project could never survive with just one of them.

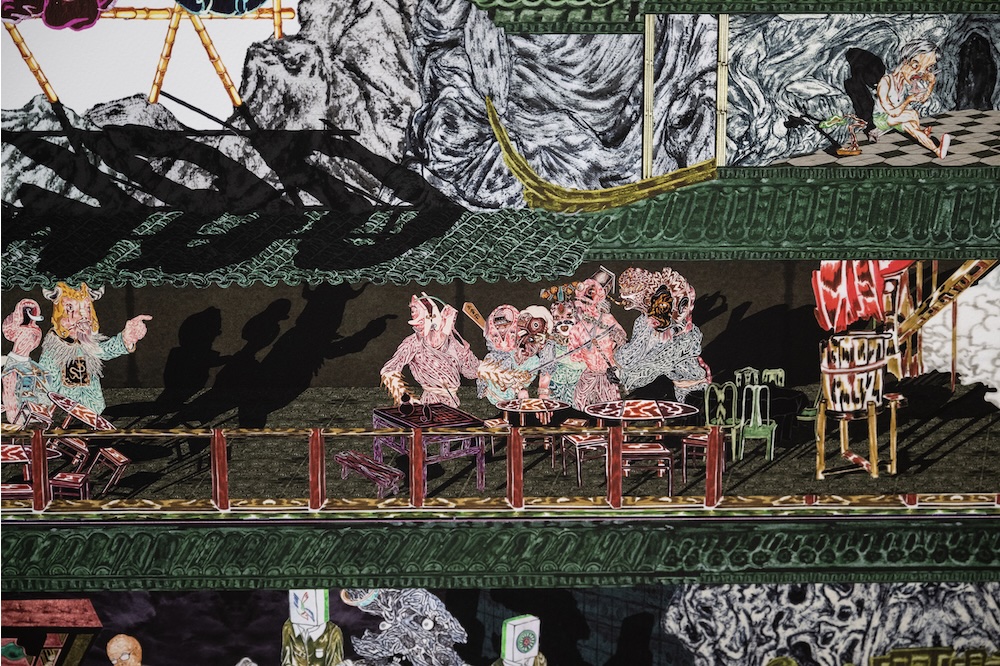

Pixy Liao, Massage Time (tribute to my favorite album cover), 2015. Courtesy of the artist, © Pixy Liao.

Story Time also encapsulates Liao’s brilliant corralling of references—nodding to an Orientalism that would objectify both her and Moro—in ways that make her meticulously crafted, funny, and horny images expansive. Another set of favorite reference points are the cultures of their home countries—China for Liao and Japan for Moro. Homemade Sushi (2010) shows Moro lying on a hotel bed, his body draped over a roll of blankets, as if he is the fish atop the ball of rice in a piece of nigiri. Other photos feature reinterpreations of onigiri, Chinese characters, and kimonos. Still others pay homage to the work of other artists—Liao’s staging intentionally references photographs by Finnish artist Elina Brotherus, a major influence, and, in one photo, Liao and Moro recreate the pose of the couple on the cover of Robert Wotherspoon’s album Music to Massage Your Mate By.

In addition to the three galleries of photos, the exhibition includes a case of sculpted penises that Liao commissioned from Morooka in 2013, a couple years into their relationship. These penises appear in some of the shots in Experimental Relationship but also stand as artworks in their own right. Liao commissioned them to explore the line between paid and unpaid work with her romantic collaborator; they are the only works in the show credited solely to Moro. There is also a screening room within the galleries where visitors can view four music videos by PIMO. The duo’s music, much like their visual art, embraces a division of labor along each partner’s strengths and desires. One song, “Absolute Monarchy,” is a groovy, light melody delivered by Liao as she embodies the character of an “SM queen,” with Moro’s voice briefly featuring as her “M man.” The song’s production subverts the straightforward message of female domination. Moro wrote the lyrics in Japanese, and Pixy, who does not speak the language, spent about half a year memorizing the words. She was, in fact, putting herself in his hands despite the lyrics and vocals that convey her dominance.

Liao and Moro’s project has evolved over a period characterized by volatile gender politics in the United States. The past two decades have seen seismic shifts—both progressive and regressive—when it comes to sexual dynamics. Gay marriage, now under renewed threat from the all-out political war on sexual difference and transness, was legalized only in 2015. Cultural figures, from online influencers to news commentators, want audiences to believe that romance is adversarial, in part because this facilitates a political climate where people are comfortable degrading others (especially women and gender minorities) even in the most intimate spheres. In this climate, it is almost impossible for real partnership to survive and flourish, making Experimental Relationship, and the way it champions humanism and play, all the more powerful. The project resists the traditionalist affective politics that threaten to swallow our most intimate relationships whole.

Liao has publicly resisted the label “feminist” more than once, and perhaps the fact that people so desperately want her to be one is indicative of how misogynistic Western gender politics have become. When progressive, feminist viewpoints are systemically repressed, even the tenderness of a loving relationship in which a woman takes a leading role is interpreted as political transgression. Regardless of its capacity for political challenge, Relationship Material lends the performance of gender and intimacy a sense of excitement and fun. In this stifling environment, a playful and rich project that suggests a man and a woman could bend normative relationship expectations within their own lives feels like a breath of fresh air.