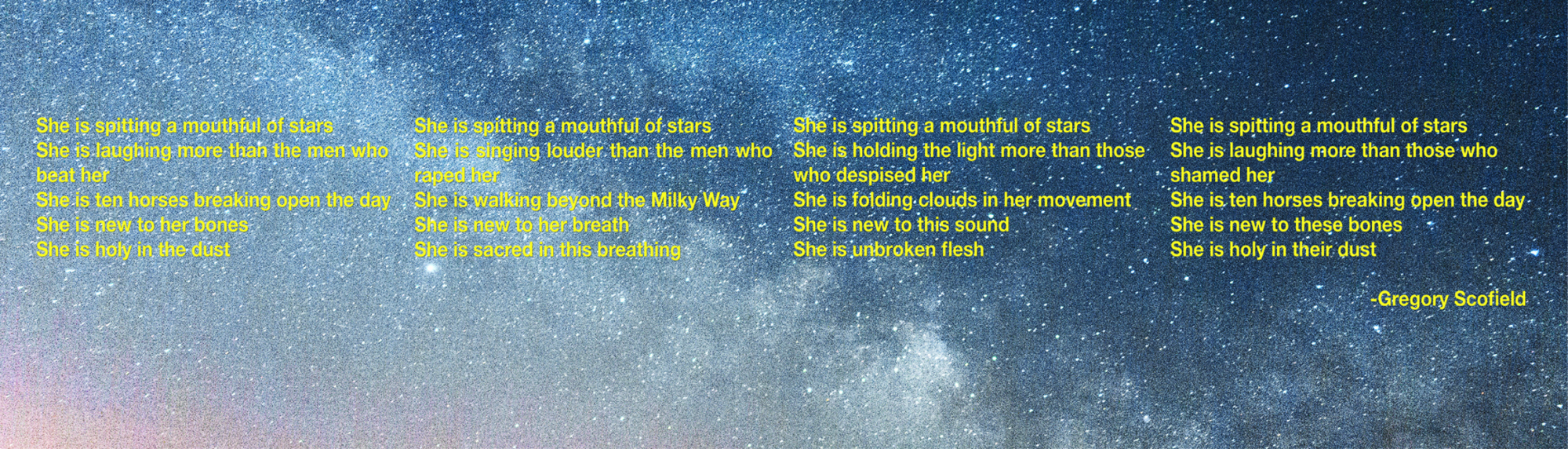

How can – how should – the ghosts of our brutalized bodies be ushered into public space? This was the enigma posed by Gregory Scofield’s She is Spitting a Mouthful of Stars (nikâwi’s song). For two winter months, the poem could be read on a billboard above Saskatoon’s AKA Artist-Run. Comprised of yellow lines over a chalk-dust starscape, it described ten actions, undertaken by an enigmatic “She.” Public texts compel collective negotiations of meaning – and in this city, Scofield’s “She” bears weight.

The Cree, Metis, and Scottish poet wrote his text thinking of the innumerable (and officially uncounted) Indigenous women murdered and abducted in Canada. While omission of a proper noun lends the work a spectral effect, the poem’s absence of violence issues an urgent corrective. Scofield’s affirmative tone breaks open the paralyzing lexicon we often use to describe atrocities.

During a discussion of Thomas Hirschhorn’s recent project at the Remai Modern, a seemingly well-meaning white visitor referred to the Indigenous population as “broken.” Understandably, the comment rankled. Even the word “atrocity” contrasts with the tenderness of Scofield’s apparent care for these victims. His approach is first evident in the way killings and abductions are only latent within the poem, which opens:

She is spitting a mouthful of stars / She is holding the light more than those who despised her / She is folding clouds in her movement / She is new to this sound / She is unbroken flesh …

This “despising” sentiment, and this still “unbroken flesh” are the closest Scofield will bring us to physical violence. We’ve had enough of that, he implies. Like the cosmos underlaying his poem, the words sparkle affirmatively.

Gregory Scofield, “She is Spitting a Mouthful of Stars (Nikâwi’s Song),” 2018, installed at AKA Artist-Run, Saskatoon.

For any person familiar with the work’s location, though, this heaven-bound “She” resonates awfully. Twentieth Street, AKA’s home, is the thoroughfare of Saskatoon’s largely Indigenous inner city. To divert one’s path from this now-gentrifying strip, with its bourgeois juice and espresso bars, is to glimpse – though certainly not to completely understand – First Nations life in the urban core. It’s from cities like this, and not rural reservations, that women tend to be stolen.

By way of context, a regrettably brief summary of this slow-burning tragedy: the grotesque rate at which Canadian Indigenous women are abducted and killed has been long-matched by the abject failure of Canadian citizens and law enforcement to respond effectively. Victim testimonies have been given. Families have marched. An inquiry requested by the United Nations has been initiated but is by all accounts a shambles, unable or unwilling to respectfully engage the affected communities and families.

Which returns us to Scofield’s poem, as it encounters this gradual murder of Indigenous women – one of whom was his aunt – in tones of esteem. Who else but celestial beings can spit stars, become “ten horses breaking open the day,” live “holy in their dust?” But in her spitting and laughing, Scofield’s “She” also displays signs of humor and spite – human complexity persists, even in tragedy.

Demonstrably, white North America’s regard for Indigenous human beings isn’t typically characterized by affection: care is registered by action, not exculpatory lip service or plaintive white guilt. Considering this selective empathy as the fulcrum of colonial violence, I recalled something the poet Susan Howe wrote in her 2015 essay “Vagrancy in The Park.” On a “clear night in February” Howe fixes her gaze on a star, and adapts a familiar recitation to her own loved ones:

Star light, star bright, / first star I see tonight. / I wish Becky, Mark, David, Peter and I won’t die until we are very old.

With that, the poet expresses faith in the protective power of stars. One might surmise it to be a power that watches over all of us equally. But Scofield’s poem – wrought from the trauma of racist and sexist killing – suggests a deep inequality in the relative ability of different people to believe in cosmic protection. Poetic echoes clash, as Howe writes: “meaning through measure may be transmitted from one generational folklore to another.” But whose folklore? For years, Indigenous survivors of colonialism have explained how their patrimonies have been vexed by trauma, as much as lore. The effects of abuse – most acutely Canada’s disgraceful “Residential schools” – echo through generations, producing poverty and acute vulnerability.

Scofield’s poem affirms the power of storytelling and mythology to affect lives across complex racial boundaries. Looking up at the billboard, passers-by may have thought of Tina Fontaine, the Anishinaabe teenager whose alleged killer was recently acquitted; or of Colton Boushie, killed last year by a white farmer who delivered a bullet to the back of his head and also escaped conviction – a failure of justice as devastating as it was predictable.

The temptation to describe this situation as hopeless calls to mind Cornel West’s recent rhetorical barrage, directed at Ta-Nehisi Coates. West’s censure emphasized the language with which racial brutality is addressed: whether it’s accepted or contested, passively absorbed or proactively fought. West claimed that Coates had fetishized white supremacy; by adopting an anguished voice, the charge read, Coates had exacerbated a narrative of victimhood rather than bolstering the capacity of African Americans to “fight back.” In response, the younger writer offered examples of his own critiques directed at the relationship between capitalist power structures and racism, as well as Barack Obama’s murderous drone campaigns. All the same, West’s larger point was made; though a perfectly human response to tragedy, despondency can be a tool of writerly fetishization: prone to devolving into an opioid melancholy that blocks our capacity to analyze and act. She is Spitting a Mouthful of Stars gives poetic voice to the ethos of resistance called for by West. Its serene, starry backdrop does not diminish its fighting power. Quite the contrary: Scofield’s reverence for Indigenous souls, callously and idiotically slighted, has both truth and morale on its side.

Resistance takes mysterious and sometimes beautiful forms – here, in so many incantations, written over starlight. This isn’t to suggest that we should elide the profound ugliness that occasioned it: “starlight tour” was also the name given to the Saskatoon police practice of abandoning Indigenous men in the rural, often-deadly winter night. It was -28 degrees Celsius on the night that Neil Stonechild was killed in this manner.

As much as violence itself, though, the lives taken call for un-forgetting. Admittedly, this is a strange verb. But it seems more useful than plain “remembrance.” Better than passive recollection, unforgetting suggests an ability – shared with Scofield’s poem – to proactively change the linguistic conventions through which lives disappear – or remain.